I recently processed 2 boxes of files from 1990-1993, which contain the files of Fred (elsewhere known as Ephraim) Weinstein. Fred had been the Director of the Latin American headquarters for HIAS, based in Rio de Janeiro from about 1958 to 1988. (He is listed in the 1986 annual report as the director of the Latin American Operations, but that is the last mention I have found of him in the annual reports.) There is a short gap in records by or about Weinstein until 1990, when he resurfaces in the New York office, in the Overseas Operations department, as the Director of Latin American Affairs.

His files contain mostly correspondence between Weinstein and members of the Jewish communities in various Latin American cities, and with colleagues in New York including Dail Stolow, who became Director of Overseas Operations in 1991, and several files of Latin American country reports he sent to HIAS presidents and others. There are also subject files on many Latin American countries, with correspondence and many newsclippings from both US and Latin American news sources. There is, as expected, a mix of English and Spanish material, and one correspondent seemed to write exclusively in French.

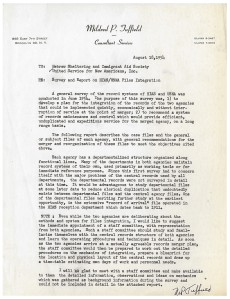

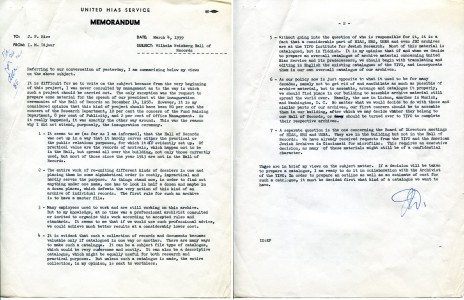

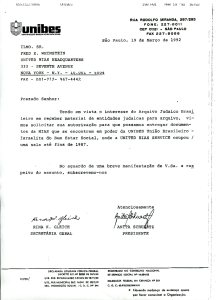

One of the most interesting documents that turned up, at least for this archivist, is this 1992 memo from Fred Weinstein to Dail Stolow, letting Dail know the plans for the files from the Sao Paulo office and the Rio de Janeiro office. One can only hope that the transfers were made to Brazilian repositories and have been kept safe over the past 25 years.

Weinstein’s memo also mentions a plan to transfer some of the Rio de Janeiro office records to “the Jewish Museum”, most likely in Rio de Janeiro.

Anyone needing more information about HIAS’ work in Latin America from the 1950s to the 1980s may be able to follow the clues here in order to locate the HIAS files. Fortunately, the Jewish Brazilian Archives in Sao Paulo (Arquivo Historico Judaico Brasileiro), has a very current website: http://www.ahjb.org.br/

A certain amount of information on HIAS work in Latin America can be pulled from the records in our collection (particularly the Executive Vice-President files and even the excellent country summaries in the annual reports), but for the overseas files themselves travel is probably required.